Understanding neural networks- Part I

Before diving into code, it’s essential to understand how a neural network is structured. At its core, a neural network is a system inspired by the human brain, consisting of layers of interconnected “neurons” that process data. This will be a three-part series describing each steps to understand a feedforward neural network. We’ll go through each steps below to successfully understand the basics of a neural network

- Defining neural network structure

- Initialize model parameters

- Forward Propagation

- Compute cost

- Back propagation

- Update parameters

- Training the model

- Predicting the model

In this post we’ll cover the first two steps-designing our neural network and it’s initial state.

Step 1: Defining the Neural Network Structure: Understanding Layers

1. Input Layer

The input layer is the first layer of the network and serves as the gateway through which raw data enters the model. Each neuron in this layer represents one feature or attribute of the input data.

For example, if you’re working with a dataset of handwritten digits (like the popular MNIST dataset), each image is typically 28×28 pixels, resulting in 784 input features (since 28 × 28 = 784). So, your input layer will have 784 neurons, each one receiving the pixel value of the corresponding location in the image.

2. Hidden Layers

Hidden layers are the intermediate layers between the input and output layers. These layers are where most of the computation happens. Each neuron in a hidden layer takes inputs from all the neurons in the previous layer, applies a weighted sum, adds a bias, and then passes the result through an activation function (like ReLU or sigmoid) to introduce non-linearity.

The number of hidden layers and the number of neurons in each is up to you. A single hidden layer can work for many simple tasks, but more complex problems often benefit from deeper networks with multiple hidden layers.

3. Output Layer

The output layer is the final layer of the network, and its structure depends on the task you’re solving:

- For classification, the number of neurons equals the number of classes. For example, classifying digits 0–9 means having 10 output neurons, each one representing the probability of a particular digit.

- For regression, typically there’s just one output neuron, giving a continuous numerical value.

Example We’ll Use: A Simple Binary Classifier

Let’s say we want to build a neural network that predicts whether a customer will make a purchase based on four input features. Let’s define a few training examples to show what the network will learn from. Each training example consists of 4 input values and 1 target output. In practice, these inputs would be normalized to keep the values between 0 and 1 for better learning performance. Let’s look at a sample of what this training data might include:

| Age | Income | Browsing Time | Items Viewed | Purchase? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1 |

| 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0 |

| 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1 |

| 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 |

Let’s look at each of the input features:

- Age (normalized between 0 and 1)

- Annual Income (normalized)

- Browsing Time on Website (in minutes, normalized)

- Number of Items Viewed (normalized)

The target output is straightforward: 1 indicates a likely purchase, while 0 predicts no purchase. This normalized format optimizes the learning process and helps our network identify patterns more efficiently. Notice how examples with higher browsing time and more items viewed tend to result in purchases - these are exactly the kinds of patterns our neural network will learn to recognize.

Network Architecture

For our customer purchase prediction model, we’ll implement a straightforward 2 layer neural network architecture:

- Input Layer: 4 neurons (each corresponding to one input feature)

- Hidden Layer: 3 neurons (fully connected to all input neurons)

- Output Layer: 1 neuron (outputs a value between 0 and 1 — interpreted as purchase probability)

This architecture is technically considered a two-layer network in modern deep learning terminology, as the input layer doesn’t perform calculations but simply passes data forward. A schematic representation of the NN is shown below.

When examining training data, we denote the \(m^{th}\) training example for the \(i^{th}\) input feature as \(x_i^{(m)}\).For neuron activations, we use \(a_i^{[l]}\) to represent the output value of the \(i^{th}\) neuron in layer \(l\) after applying the activation function. More generally, we can represent a neuron in any adjacent preceding layer as \(a_i^{[l-1]}\).

Great! Now that we’ve defined the structure of the neural network, the next step is to initialize the parameters — specifically, the weights and biases. These parameters are what the network will learn during training.

Step 2: Initializing Parameters – Weights and Biases

Every connection between neurons in adjacent layers has a weight, and every neuron (except those in the input layer) has an associated bias. These are the values that the network updates during training to reduce the prediction error.

What Are Weights?

Weights determine how strongly an input influences the output. Each weight connects a neuron in one layer to a neuron in the next layer.

- If a weight is large and positive, it strongly activates the next neuron in the next layer.

- If it’s negative, it inhibits the next neuron.

- If it’s close to zero, the input has little effect.

What Are Biases?

The bias is an extra parameter added to the weighted sum before applying the activation function. It allows the neuron to shift the activation function, enabling it to learn patterns that don’t pass through the origin. Without biases, the neural network’s flexibility would be significantly limited.

How to Initialize: Matrix representation

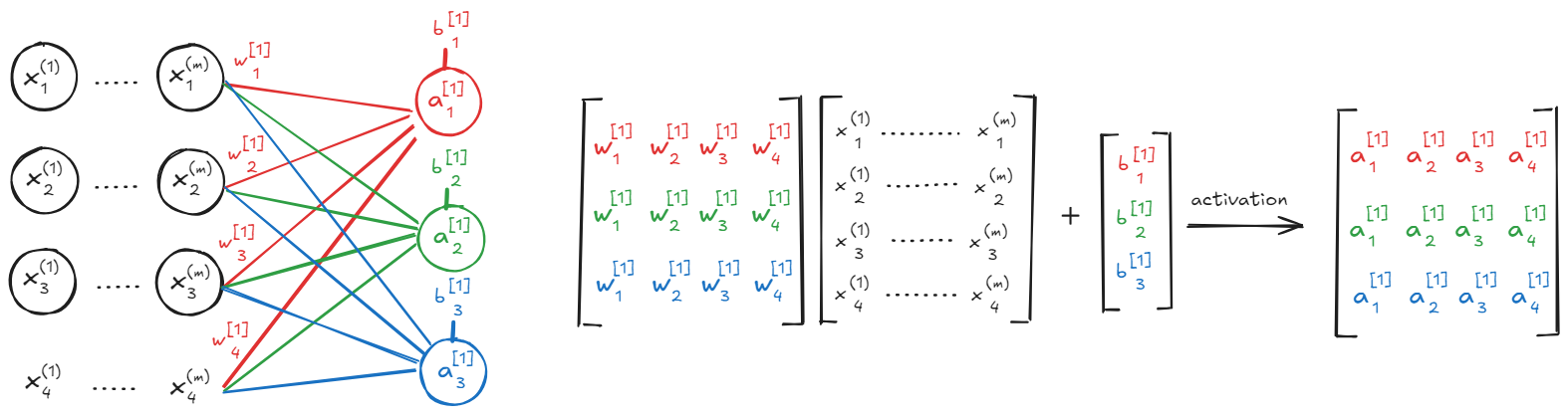

Let’s start with a visual. Imagine our neural network with an input layer and a hidden layer, as shown in the diagram.

Consider the connections between our input and hidden layers. While a single input observation might be shown in a schematic, thinking about the entire training data in the input layer is essential for understanding how matrix operations power neural networks.

At the core of every neural network connection are weights, learnable parameters that define the strength of the connection between neurons. Alongside weights, biases provide an extra degree of freedom for the network to learn. To make the connections clearer, we’ve color-coded the weights, biases, and the resulting neuron values in the hidden layer in our diagram.

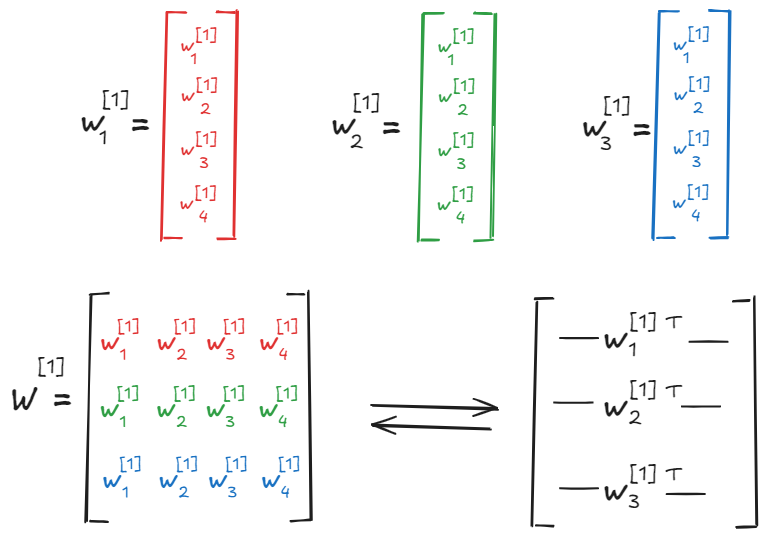

To clarify the upcoming calculations, let’s refine our notation For a given layer \(l\), the weights connecting to neuron \(i\) are represented as a vector \(w_i^{[l]}\). The subscript \(i\) indicates the neuron receiving the weights, and the superscript \(l\) indicates the layer. This is shown in the figure below. Similarly, the activation of neuron \(i\) in layer \(l\) is represented as \(a_i^{[l]}\). For example, \(a_1^{[1]}\) represents the activation of the first neuron in the first hidden layer.

For a single neuron, say the first neuron in the first hidden layer \((i=1,l=1)\), the input to this neuron before the activation function, often denoted as \(z\), is calculated as the weighted sum of the activations from the preceding layer (\(a[0]\) represents the input layer activations) plus the bias term (\(b_1^{[1]}\)):

\[z_1^{[1]}=w_1^{[1]T}a^{[0]}+b_1^{[1]}\]This value \(z_1^{[1]}\) is then passed through the activation function, \(g(z)\), to get the activation of the neuron:

\[a_1^{[1]}=g(z_1^{[1]})\]More generally, for neuron \(i\) in layer \(l\), the calculation is:

\[z_i^{[l]}=w_i^{[l]T}a^{[l−1]}+b_i^{[l]}\] \[a_i^{[l]}=g(z_i{[l]})\]While understanding individual neuron calculations is important, neural networks primarily leverage linear algebra to perform these computations for an entire layer simultaneously. This is where the matrix representation becomes invaluable.

We can calculate the \(Z\) values for all neurons in layer \(l\) using the weight matrix \(W^{[l]}\) (where each row is a weight vector \(w_i^{[l]T}\), the activation matrix from the previous layer \(A^{[l−1]}\), and the bias vector \(b^{[l]}\):

\[Z^{[l]}=W^{[l]}A^{[l−1]}+b^{[l]}\]Notice the difference in how the weight matrix \(W^{[l]}\) is used here compared to the single neuron equation. In the matrix equation, \(W^{[l]}\) is structured so that when multiplied by the activation matrix \(A^{[l−1]}\), it simultaneously computes the weighted sum (\(w_i^{[l]T}a^{[l−1]})\) for every neuron \(i\) in layer \(l\) across all training examples. This single matrix multiplication efficiently performs all the necessary dot products at once!

Finally, applying the activation function g element-wise to the matrix \(Z^{[l]}\) gives us the activation matrix for layer \(l\), \(A^{[l]}\):

\[A^{[l]}=g(Z^{[l]})\]This matrix \(A^{[l]}\) then serves as the input activation for the next layer’s calculations. This matrix-based approach allows for highly parallelized and efficient computation, which is fundamental to training neural networks on large datasets.

Understanding the Parameter Shapes

The dimensions of these matrices and vectors are crucial for ensuring the math works out. Let’s define the shapes for our specific example network (with 4 input neurons, 3 hidden neurons, and 1 output neuron) and then generalize:

- Input Layer → Hidden Layer (Layer 1):

- Weights (\(W^{[1]}\)): This matrix contains the weights connecting the 4 input neurons to the 3 hidden neurons. Its shape is (3, 4).

- Biases (\(b^{[1]}\)): There is one bias term for each of the 3 hidden neurons. This is represented as a vector of shape (3, 1).

- Hidden Layer → Output Layer (Layer 2):

- Weights (\(W^{[2]}\)): This matrix connects the 3 hidden neurons to the single output neuron. Its shape is (1, 3).

- Bias (\(b^{[2]}\)): There is one bias term for the single output neuron. This is represented as a vector of shape (1, 1) (or simply a scalar).

Generally, the weight matrix \(W^{[1]}\) has the shape (\(n_h^{[l]}×n_h^{[l-1]}\)), where \(n_h^{[l]}\) is the number of hidden units in layer \(l\) and the bias vector \(b^{[1]}\) has the shape (\(n_h^{[l]}×1\)). The activations of a given layer will be a matrix of shape \((n_h^{[l]}\times m)\) where \(m\) represents the number of observations being fed through the network.

So, the next time you encounter a neural network, remember the elegant matrix operations happening under the hood. This fundamental understanding is your key to building and training more complex models!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: